A Couple Walks Up the Logging Road

Ruby Hansen Murray

Mid-morning in early summer fog haloes float off whaleback ridges along the Columbia. A skein of moisture overhead promises to cool the day a little longer.

Near the river, the valley is open to thigh high grass and skunk cabbage leaves, to the nubbed arms of fir coated with moss. A fringe of lichen, the small starry hands of vine maple, swordferns, blades of grass.

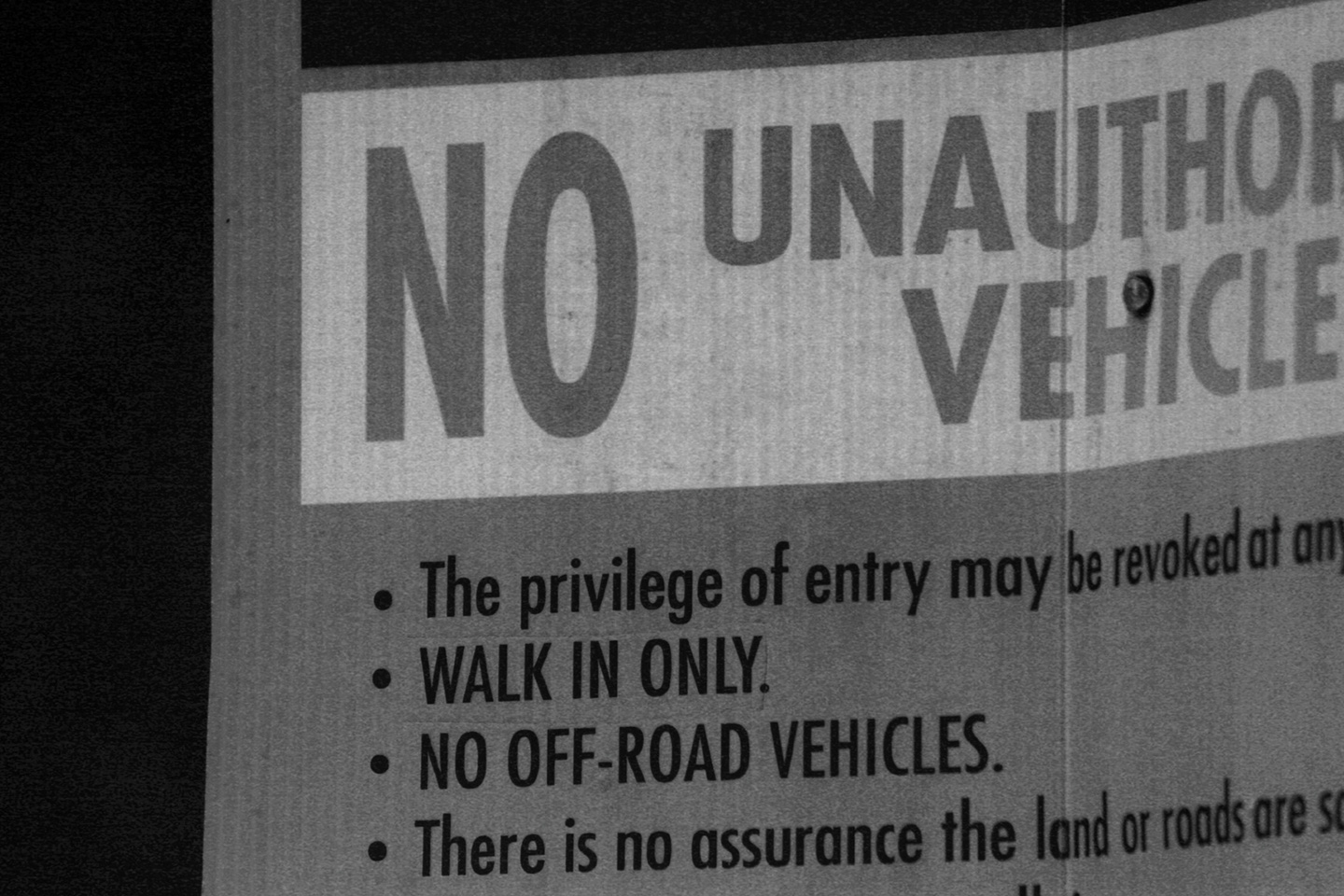

We park at the juncture of roads that lead up Nelson Creek or Alger Creek and walk to the locked metal gate where Campbell Global has posted a list of rules. It’s Sunday, no log trucks will pass, no hunters this time of year.

We walk a road paved with fist-sized rock to a fork and she chooses the right. Grass in the center of the path, the rocks turn to pebbles pressed into dry ground.

We can see forty miles downriver to the blue-green mound of Tongue Point and a scrape of dredge sand piled on Tennashille Island. There’s the sweetness of white-flowered clover along the road. The pointed dark green of a thistle still wrapped like a pear with wispy threads.

His lean silhouette on the smaller cross ridge as he holds binoculars. He says, “There’s a ship at anchor.”

We watch a cargo ship’s masts move above the tips of the firs along the river. Two blasts of a horn, although we can only see a fishing boat no larger than a white cap.

He wants to see a snake and a bear. Honey bees and a bumblebee nectar

along the road. She wants to lose weight, to float up the hill, to walk all day.

We name the points, knobs with scraggly trees like a cowlick. Crown Point, Wickiup, Skamokawa. Power lines and a tower.

He steps over one can, rusted flat. No glinting Clamato and Bud cans.

Along the ridge, she looks down the steep incline into the lower branches of 100-foot tall Doug fir. In the great emptiness along the river, bald patches of dirt, clear-cuts.

“You know you can’t have large life-less patches anymore,” he says. “It’s against the law.”

As if we need environmentally friendly clear-cuts. On the ridge across, one tree left standing, so tall it looks like a spar. Some yards away a shorter tree. Leave trees for mitigation.

On the way back to the truck, down the rolling pebbles and ankle-turning rocks, a black lump of licorice slug.

She looks for shadows on the near ridges, but finds no elk or deer, bobcat, skunk, raccoon or possum. Tire treads dried in gray silt.

He says, “If we had taken the other road, we would have connected with the road on the next creek.” He draws the road to the north in the air. “Around that curve is where I saw the cougar.”

John Hoven—with his beard curling down his chest—said, I’m sixty-four and I’ve seen two cougar and five bears in my life.

A chickadee flies across the road. When she hears the five note call, she repeats it, waits for the reply, while they walk down hill, the stub of her toes against her shoes.

An inch-long dragonfly. A glint of blue on gravel, a burst of jay above soft-gray-frizz. He carries the feather between his thumb and the glass of his phone.

She says, “Salmon berry.”

He points and says, “Oregon grape.”

A pause. “Salal.”

“Aren’t they the same?” He asks.

Mahonia aquifolium, she thinks, smelling the yellow stickiness of it.

“No, Oregon grape has pointed leaves.”

He looks for language they can speak, for a project, for joy. She studies the sides of the road for paths the elk might have taken. She wants to bring a chair, a picnic lunch, to walk into the woods left standing, to smell the ground where the elk rested.

Off Risk Road, white windows on a shingle wall, a porch the length of the house, two chairs ready for evening. The diesel engines of ghost trucks and men shouting.

Originally published in Moss: Volume Four.

‹ |

Previous First Lady, Anis Gisele |

Next Be Okay It Will Be Okay, John Englehardt |

› |